The state of social housing in Western Australia: Ideas and innovations for the future (part 2 of 2)

blog | Words Kaci Oliphant | 09 Aug 2021

Making meaningful changes to the state of social housing in Western Australia requires a combination of scaling the solutions we know work, and using innovation to develop new solutions that serve the most vulnerable in our communities.

Across Australia and around the world, governments, social and private enterprises are developing new solutions to the growing challenge that acknowledges housing as one element of a broader ecosystem: interconnected with other services and structures, and significantly impacted by shifts in these spaces. In part 2 of this blog, we will explore the features of new solutions to the housing crisis, and share some examples of innovations in social housing and programs working to address homelessness from around the world.

PROMISING SOLUTIONS TO EXPLORE AT SCALE

Here’s a look at some examples from Australia and countries across the globe that are seeking to ensure everyone has a safe and supportive place to live:

HOUSING FIRST (GLOBAL)

The Housing First model is a strategic response that prescribes permanent, stable, and safe housing as the first priority for people experiencing homelessness. With the Housing First approach, the innovation lies within the basis of providing housing ‘first’, as a matter of right, rather than ‘last’ or as a reward. It is based on the belief that there should be no extenuating conditions around ‘housing readiness’ before providing someone with a home. Instead, secure housing is viewed as a stable platform from which other issues can be addressed. Individuals don’t lose their housing if they disengage with support, and flexible support is provided for as long as it is needed and remains even if the tenancy fails.

Originating in the US, Finland was an early adopter of this model and has experienced significant successes; reductions of greater than 35% in long-term and repeated homelessness since 2007. Across the four main principles of the Housing First model; increased engagement with social and health services has led to improvements in wellbeing and a reduction in substance misuse. According to y-säätiö, the gap in local service provision for individuals for whom no previous services had been successful has also been addressed through integration into the community and society . This model has also served as a catalyst for wider culture and systems change, reducing the workload and pressure of service providers and the police as well as having a particularly positive impact on community safety and anti-social behaviour teams.

KEY TAKEAWAY: A shift in mindset to put housing at the centre of people’s wellbeing is needed, acknowledging in the hierarchy of needs that people can’t thrive in their lives unless they feel safe.

PEMULWUY PROJECT (NSW, AUSTRALIA)

Incorporated in 1973, the Aboriginal Housing Company Ltd (AHC) is an all-Aboriginal governed independent non-profit charity and is the first community housing provider in Australia. Formed in direct response to the widespread discrimination targeted towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the private rental market, the AHC is located in the heart of Redfern, which lies in the traditional lands of the Gadigal people, part of the Eora Nation, and has been expanded to provide affordable housing across Sydney and regional NSW. Being self-funded, the AHC operates on income derived from rental properties.

The “Pemulwuy Project” prescribes the redevelopment of land into affordable housing for over 60 Indigenous families as well as other multi-use sites such as childcare, commercial and retail space, a gym and student accommodation. The AHC retains control of the project alongside ownership of the land, having developed a sustainable business model by Aboriginal people for Aboriginal people to ensure ongoing viability. Given that the architectural design both recognises and responds to the stories of people and place where it is located; service provision has been designed in response to local people and local needs, such as providing support to Aboriginal families and the large student population.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Give agency to Indigenous organisations to make decisions about what the housing needs of First Nations people are and resourcing them properly to achieve their goals.

EMMAUS COMMUNITIES (GLOBAL)

Aimed at delivering stable and secure long-term accommodation for individuals to progress beyond homelessness, Emmaus Communities provides work and a home for residents in a supportive, family environment. Communities are set up when local people decide that the tried and tested Emmaus approach to homelessness would benefit their area. Emmaus offers a home in a Community for as long as someone needs, where people can live and work, sharing a life together, but retaining their own dignity and independence.

Companions, as residents are known, receive accommodation, food, clothing and a small weekly allowance. In return, Emmaus asks that Companions work for 40 hours a week (or as much as they are able) in the Community’s social enterprise, the Community Shop. Emmaus residents work to support themselves and to help others, with each Community aiming to become self-supporting. Sharing (or solidarity) is central to the Emmaus ethos; all the proceeds of the Community’s work go into the ‘pot’ and out of that every Companion receives their board and clothing, plus weekly spending money and savings. Any surplus created by the business is used to help those who have less. Emmaus’ varied businesses enable companions to develop skills and work toward a common goal, whilst ensuring its ongoing financial sustainability. A 2012 analysis by Just Economics across 7 UK communities found Emmaus’ work to have a high rate of social return; generating £11 for every £1 invested in the communities.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Help people feel like they belong to a community, creating a supportive environment that helps people to emotionally transition from being homeless.

THE ZERO FLAT (SPAIN)

The Zero Flat is a new type of apartment for chronically homeless people with difficulties adapting to other housing resources, including the Housing First model, due to the high degree of their social exclusion. Located in the heart of Barcelona, the Zero Flat space combines the characteristics of a night shelter that incorporate the minimal requirements for sleeping rough with the warmth of a ‘home’ to provide a new way of living that responds to the real needs of long-term homeless people. Through inclusive codesign methods and a high-level of community involvement in the design and development of the site, a space that feels and operates differently to conventional homeless accommodation has been created that values the lived experience and desires of society’s most vulnerable and marginalised groups. This has proved to be incredibly successful, as post-launch in 2017, the Zero Flat project recorded that more than 74% of its users during its first year of operation were able to improve their situation and move on to other residences.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Accommodate recurrently homeless persons with new, innovative housing typologies that look, feel and operate differently to conventional housing accommodation, to promote social inclusion in a setting that distances itself from highly structured environments that characterises most other places of support.

THE BLOCK (SEATTLE, UNITED STATES)

The BLOCK Project by Facing Homelessness aims to integrate individuals facing homelessness into supportive and thriving communities by building fully equipped and self-sufficient 125ft2 detached homes. These dwelling units are placed in homeowners’ backyards throughout Seattle neighbourhoods with residents thoughtfully matched with hosts and engaged neighbours thus creating a network of community support including access to professional social services in addition to providing safe shelter and community support. With a strategic vision to help end homelessness by building BLOCK homes in every residential block in Seattle, this intentionally inclusive service model changes attitudes towards homelessness by bringing residents, hosts and neighbours together through shared experiences; presenting opportunities for scale-up nationwide and internationally as well as creating a “foundation of compassion and empathy for future generations”.

The Block Project’s integrated, sustainable, supported, affordable and dignified approach towards tackling homelessness fosters cross-class integration and social inclusion; making use of free available property that leverages the local community’s desire to get involved thereby reducing the cost of providing permanent, stable housing for residents as they define and achieve success.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Utilize supportive and compassionate neighbourhoods with free available property to connect people who are housed with people who aren’t to work around the high cost of real estate and the stigma endured by those sleeping rough as instigated by a lack of understanding and connection (The Block).

VINZIRAST MITTENDRIN AND LOKAL MITTENDRIN (AUSTRIA)

The VinziRast project is a pilot project in the area of community living and brings together students and formerly homeless people who live together in ten three-bedroom apartments, as well as spaces for facilitating social encounters, including common rooms, a restaurant and event venues.

The VinziRast project consists of both common housing for students and homeless people (VinziRast mittendrin) as well as a space for working and meeting (Lokal mittendrin). The house is first and foremost a meeting place for the public. The restaurant Lokal Mittendrin, is an ideal place for meeting the residents. This means that the restaurant works as a social melting pot, facilitating encounters that may otherwise have never happened. Secondly, the house offers employment opportunities. The residents can work in the restaurant or attend language courses or other courses to develop their skills. There are also workshops located around the inner yard, such as bike repairs. The workshops serve the double function of helping both vulnerable people who need a job or some income, and the general public in need of help with tasks such as bike maintenance or repair. Thirdly, and most importantly, the house is a home for the residents. Each flat serves three inhabitants, one student and two formerly homeless people or two students and one formerly homeless person. A private bedroom offers absolute privacy for each inhabitant, which is important when talking about community projects. The three people share a kitchenette and other facilities together. On each floor, there are three flats and a shared kitchen and living room for the group.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Provide dignified spaces where the most vulnerable residents of the locality can access a continuum of fully integrated and on-site services including treatment, life-skills training and shelter whilst fostering social inclusion.

MORE THAN HOUSING (SWITZERLAND)

Resulting from the collaboration of over 50 different cooperatives, the More than Housing development located in Zurich provides affordable housing to over 1,200 people from a wide range of backgrounds and income levels across 400 communal and environmentally efficient apartments alongside large, shared community spaces and neighbourhood infrastructure, including 35 retail units. Completed in 2015, the project deliberately promotes social diversity and incorporates sustainable energy use. These priorities are included in the architectural design, where each of the buildings were designed to use as little energy as possible and respond to multiple needs, and in various organisational mechanisms, including management, the promotion of sustainable lifestyle changes, and the allocation of tenancies.

With the project being a financially and environmentally sustainable urban living and working space, its scale and extent make it one of the largest and most ambitious cooperative housing programmes in Europe. Further, the deliberate promotion of social diversity throughout the project in the form of architectural design, to respond to multiple needs, through management to the allocation of tenancies by engaging organisations working with different underrepresented groups and providing rent at below-market prices to a wide diversity of people, the More than Housing scheme showcases several innovations in social housing.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Challenge existing urban dwellings by considering co-operative housing to counter housing shortage and cater for the ever-constantly changing expectations of society and associated demands on living space.

BUD CLARK COMMONS (PORTLAND, UNITED STATES)

Bud Clarke Commons is a comprehensive services centre, combining a resource centre with two levels of transitional and supportive housing in an environmentally sustainable eight-story structure, to provide stability to the lives of those experiencing homelessness. Located at the gateway to downtown Portland, the project offers three distinct elements: a walk-in day centre with access to services, a temporary shelter with 90 beds for homeless men and 130 studio apartments for low-income women or men seeking permanent housing on the five upper floors. Placement is prioritised along the 10 ‘domains of vulnerability’ utilised by Home Forward, including factors such as ability to meet basic needs, nature and extent of homelessness, social behaviour and risk of mortality. Given its close proximity to existing homeless services providers, the shelter also partners with multiple agencies to coordinate the range of available services as well as providing case managers and councillors to assist residents approach self-sufficiency and ‘housing stability’.

According to data from Transition Projects, Inc, since opening, the 130 permanent housing units have effectively promoted stability; resulting in a resident retention in excess of 80%, and in the first year alone, the day centre served over 7,000 homeless people, connecting 3,600 of them with social services and providing permanent housing placements to 350 individuals.

KEY TAKEAWAY: Develop partnerships so that housing and services put the needs of residents at the centre; making it as easy as possible for them to connect with providers that are helping them in different facets of their lives.

WHAT MIGHT TRANSFORMATION TAKE?

The transformation that we need to see in the social housing sector requires a strong commitment from state and federal governments and other community stakeholders. At a system level, removing regulatory obstacles would accommodate for a greater number of homes and apartments being built and coincide with a decrease in time and cost of building thus allowing for significant progress in housing affordability.

An increasing number of incentives should also be made available for individuals to more readily qualify for mortgages or afford rental housing. For example, renters could be provided with assistance to achieve homeownership through programs designed to improve their financial literacy and position as well as increasing their credit scores.

Further, it is important to ensure that existing housing affordability schemes are not forgotten but rather preserved. Funding is increasingly required to be directed towards addressing the issue of depreciation in many neighbourhoods given that rent is often insufficient to cover the cost of maintenance.

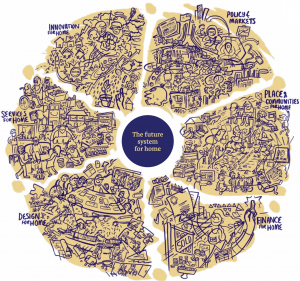

In compiling seven years of exceptional work in the innovation and housing sector, The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) having recently published their “The Future of Home” report, which identifies six principles that can be applied to policy, service and or any program that aims to shape better housing outcomes for people.

In drawing the key points from this report that have inspired new discussions about the future of housing in Australia, three main takeaways can be identified. Firstly, by prioritising the critical functions of home: agency, connection and identity; negative contributions can be limited should positive contributions to the functions of homes not be possible. Further, long-term social and economic returns associated with housing should be prioritised over short-term profits given that the principal value arises in the form of improved health, education and employment outcomes across generations rather than near term profit seeking which can often displace the critical functions of home in decision making. Finally, questioning what makes a good home in one neighbourhood contrasted to the next allows investors to account for locality and respond to local contextual practices and place by considering the potential that homes have to contribute to better neighbourhoods and vice-versa.