Ka Mua, Ka Muri

blog | 11 Dec 2019

How to look back to Te Āo Māori/the Māori world to advance your design research practices.

This is one of two blog posts based on Rachel and Kataraina’s talk at the 2019 UX New Zealand conference, which you can watch here.

Words by Rachel Knight & Kataraina Davis

Why cultural competency?

In our country, Māori face huge inequalities across key health and wellbeing outcomes. As researchers, designers, and makers, we hold a key role in shaping the products, services, and experiences offered in Aotearoa New Zealand, so we need to get better at working with and learning from Māori if we are to create positive social change in our communities. We also know that generally, what is good for Māori is good for everyone.

Four pou/values

At Innovation Unit Australia New Zealand, we are committed to actively decreasing inequalities with and for Māori, and over the past 7+ years we’ve been on a journey to develop our cultural competency as a team of social innovation practitioners. We know this is an everlasting journey with no end and no right or wrong way, but below are four key pou/values that we apply in different ways in our day to day in the office, and externally in our mahi/work:

1. Whanaungatanga

Essentially means ‘becoming family’ by prioritising building and maintaining relationships.

2. Manaakitanga

Often translated bluntly to ‘hospitality’, it means to enhance others’ mana (power/respect that others have for you) through safe, welcoming and accessible spaces and processes where people can participate meaningfully.

3. Kaitiakitanga

Guardianship. Often referred to in relation to being a guardian of natural resources, but can also extend to being a guardian of people, thoughts, processes, stories, and ways of being.

4. Ako

Ongoing and reciprocal learning.

All four pou are interconnected, and none hold more mana/importance than the others. They are largely universal values that aren’t just relevant for working with and for Māori, but can also help you reflect on and improve your practice – or just be a better human. You might also find that some come more naturally to you, while others will take hard work and practice.

What they can look like in practice and what we’ve learnt from applying them to our work

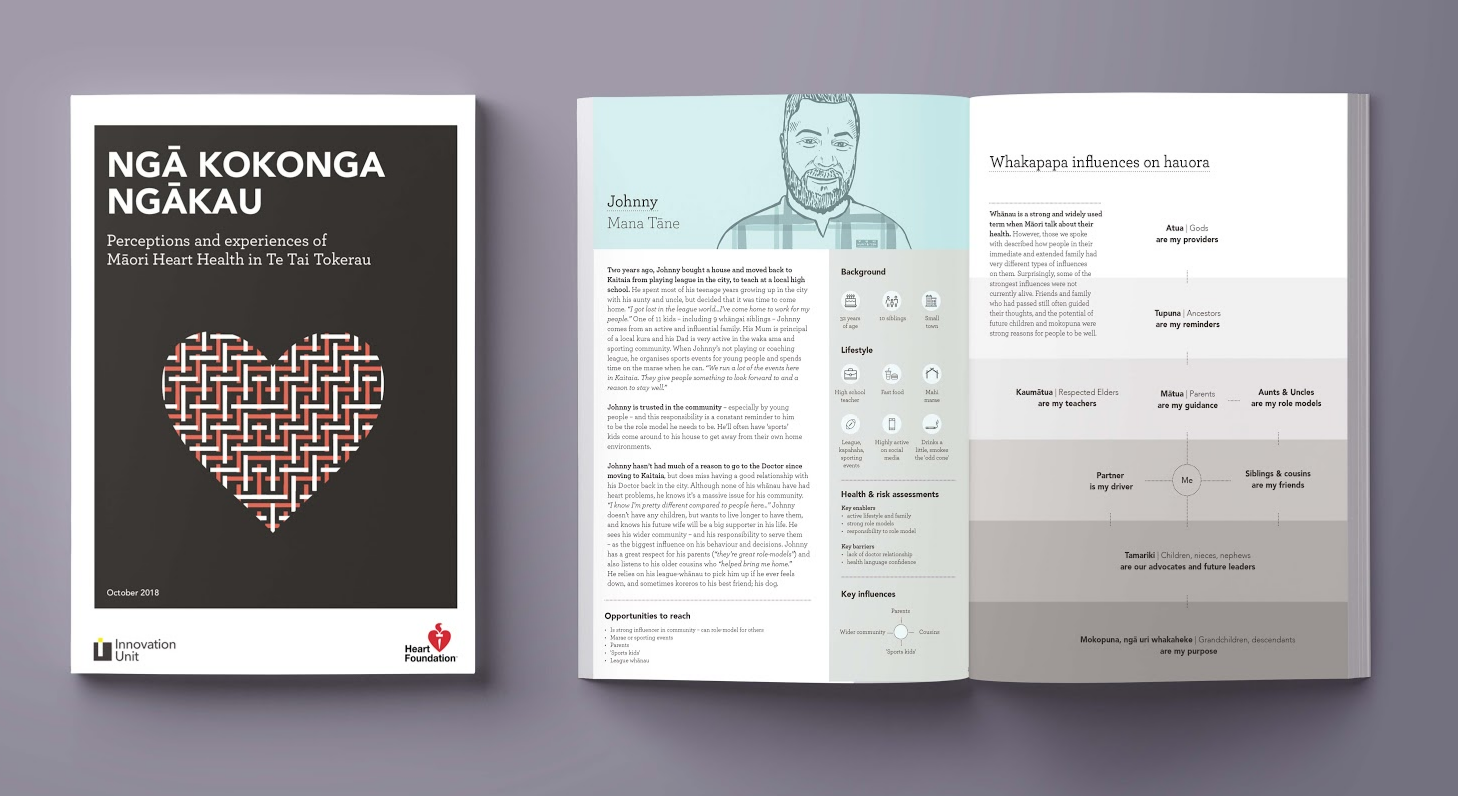

We apply all four pou in many different ways in all of our projects, but recently we had the opportunity to dive more deeply into Te Āo Māori with a project we did in partnership with the Heart Foundation of New Zealand. The project, later named Ngā Kokonga Ngākau, was to support the Heart Foundation to understand how they could improve access for Māori – partially Māori men – in the Far North to earlier heart disease risk assessments.

We started by doing a literature review of recent local and international research, then went on a road trip across Te Tai Tokerau (Far North of New Zealand) to talk with Māori about their perceptions and experiences of heart health for themselves, their whānau/family and wider community. We then moved into co-designing new potential solutions with whānau and health professionals. Below are some ways we applied each pou in the project, what we learnt from it, and some wero/provocations for you to consider in your own work.

Whanaungatanga | Relationships are important

Our projects would not be possible without the people we work with and learn from, so building relationships is a key part of every project we work on.

IN THIS PROJECT IT LOOKED LIKE

Maintaining existing relationships before we needed them. For this project, Kat drew on some of her personal relationships in the Far North to connect with individuals and families that we never could have reached without going through those trusted relationships. Whanaungatanga means making the time to prioritise staying in touch and keeping relationships warm – instead of only going to people when you need something.

WHAT WE LEARNT

Seeing Kat apply whanaungatanga in this project made me reflect on my own approach to design research. It made me realise that the approach I’ve learnt has been quite clinical and pākeha centric, where we keep a ‘safe’ distance between ourselves and research participants. The problem with that approach is that you can also distance yourself from responsibility of creating change based on those conversations because at the end of the day, you could probably walk away and never see those people again. This can break down trust not just in yourself as a practitioner, but also in the processes you use. However, when ‘participants’ just become ‘people you know’, there’s much more personal accountability and motivation to follow through.

Wero / Provocation to you

What’s your organisation’s budget for cups of tea?

Keeping relationships warm takes time, but it’s an investment. So how is your team enabled to build relationships and stay in touch with people in an ongoing way? And how do your research processes prioritise building relationships, rather than treating people in a clinical, transactional way?

Manaakitanga | Enhance others’ ‘mana’

Co-design is all about enabling a power-shift in the dynamic between people who provide solutions or services, and those who might benefit from them. Showing manaakitanga is essential to make sure these power dynamics are addressed and that everyone can safely participate.

IN THIS PROJECT IT LOOKED LIKE

At a basic level this meant recognising the value of peoples’ time and whakaaro/thoughts with kai/food and koha/gifts, and making sure we followed the tikanga/conventions of people’s homes.

It also meant using processes that resonated with the people that we spoke with – but staying agile enough to change them if they weren’t working. We originally started by using a discussion guide based on a Māori Health model, but quickly found that this didn’t necessarily resonate well with the people we were speaking with. Instead, we changed the questions to start with a simple ‘Tell me about the whakapapa/history of your experience with heart disease?’. By using more relatable words, we were able to have deeper conversations with the people we met.

Later in the project when we moved in co-design, it meant creating safe spaces in a workshop setting for people from very different backgrounds to come together and learn from each other.

“You brought together a group of people you’d never see in a room together and made it possible to work with each other and everyone felt safe. You steered that ship. We can’t take it for granted that I would walk into a space I know nothing about and feel safe. Your assistance in supporting me was huge. You helped us to be a part of that.” Tony Duncan Then CEO of the Heart Foundation

WHAT WE LEARNT

Don’t ever assume how connected people are to Te Ao Māori/the Māori world.

Because many Māori have inherited a disconnection from Te Āo Māori (see: colonisation), many are on the journey of reconnecting with their past, and the journey can come with plenty of hurt. Although to one person, using Te Reo Māori might be mana-enhancing, to others it might bring about feelings of whakamā/shame. The best thing to do is to meet people where they’re at, and give them options to engage in ways that are comfortable for them.

Wero / Provocation:

How do your processes enhance people’s mana?

Kaitiakitanga | Guardianship

When you conduct research, you become a kaitiaki/guardian of the people you talk with, and the stories they share with you. Upholding the up-most respect for their taonga, their treasures, is so important to maintain trust.

IN THIS PROJECT IT LOOKED LIKE

Closing the loop and sharing back what we took.

This meant sharing back the research report with those involved and making sure they had the opportunity to shape any potential solutions moving forward, as essential partners in the process. It also meant treating their stories like taonga/treasures, in the way that we wrote and presented them – and testing these back with people to make sure we had fairly represented what we had heard.

It also looked like upholding tikanga Māori, not picking and choosing.

It’s important that we don’t just pick and choose the parts of tikanga Māori we like and leave the rest. As a kaitiaki of tikanga Māori, it was Kataraina’s role to uphold these processes and make sure everyone else was able to safely follow.

“The codesign workshop didn’t feel like any that I’ve been in before because of the level of tikanga. It felt really deep. It’s also a higher pressure in case you break tikanga. It takes Māori leadership, and it’s reinforced my belief that we need more Māori leadership in this space.” Aimee Hadrup

Director Innovation and Impact, Innovation Unit Australia New Zealand

WHAT WE LEARNT

1. The benefits of sharing back information generally outweigh any risks.

The whānau involved really appreciated it, and when we made the report public on our website, we were told that other designers had used it in their work to shape their approach for a new project. The true value of insights are often unintended, when you share them and create ripple effects and positive impact wider than we could ever create on our own in the one project.

2. Invest fully in tikanga, it will ‘pay off’ later on.

Fully investing in Māori processes can ‘pay off’ for those you’re serving, by creating connections that resonate with whānau Māori. It can also ‘pay off’ for your overall process by helping you build whanaungatanga and rapport, and generating future buy-in from whānau.

Wero / Provocation:

What’s your organisation’s commitment to sharing back people’s stories?

With the rise of co-design, too many people – especially whānau Māori – are being asked about their experiences but not seeing what happens with the data. Why take someone’s taonga if you know you can’t give it back? Let’s stop worrying about worst-case scenarios around sharing information, and Instead imagine what the positive knock on effect could be.

Ako | Ongoing reciprocal learning

Learning new information always comes with doing research, but how can we give back as well as take?

IN THIS PROJECT IT LOOKED LIKE

A Tuakana / teina relationship between myself and my colleague Kataraina.

Tuakana / teina means a reciprocal learning relationship between an older and younger sibling, where the first teaches the other about the world, and the latter often teaches the other patience. Kat and I had this relationship, where Kat was the Tuakana of Te Āo Māori, and I was the Tuakana of design. A highlight for me was sitting on a beach in Paihia, starting to make sense of the research together, and having some really deep talks together about the overlaps and tensions between these two worlds.

WHAT WE LEARNT

Our strength lies in our differences.

Kat and I are very different people and practitioners – we’re like chalk and cheese – and this means we compliment each other, and learn from each other every time we work together.

Wero / Provocation:

What are you bringing to the table of reciprocity? What are you bringing to teach, and what are you open to learning?

Impact for practitioners, partners, participants

The ongoing impacts of this project in shaping the Heart Foundation’s approach to risk assessments and more broadly how they better serve Māori is still in progress, but as is often the case with these projects, the immediate impact was on the people involved.

Practitioners:

Deeply applying these four pou in this project meant we were able to have deeper conversations and explore areas with people that we didn’t think even know we’d be exploring. In turn, this meant we could tell better, richer stories about this issue and how it affected people on multiple levels.

Partners:

Strong storytelling meant we were able to help our project partners experience a deep emotional response, and feel safe to take off their expert hat and instead step back to listen and learn from people with lived experience.

“The storytelling was very powerful, to the point that I became so emotional learning about the people and their life outside of cardiovascular disease….The biggest picture was entering into a world I knew nothing about. I understood Māori morbidity and death rates but the Māori world view about whānau, and death, and how far into the future, and how far back Māori people feel connected – this is all new to me… It all came into my heart in a way it hasn’t before…I can picture these people. I’ve got them in my head now.”Tony Duncan Then CEO of the Heart Foundation

Participants:

With our project partners stepping back and listening, we were able to create a space for whānau to shine in their deep knowledge and expertise. We saw a strong power shift in mana, where the whānau became the designers of future heart disease solutions for their communities.

So, kua takoto te manuka – we’ve laid down the challenge for you. What have you learnt from applying Te Āo Māori values in your work? We’d love to hear your thoughts and pātai/questions. Or, if you’d like somewhere to start, you can download this booklet here.

Watch Rachel’s and Kataraina’s talk here: