Disruptive learning in and from a crisis

blog | 13 Jan 2021

Learning from innovation in a crisis: how the disruption of Covid has given Greater Manchester the chance to ‘design forward differently’

Over Christmas, Stephen Fry’s 21st Century Firsts covered some of the landmark events from the first 20 years of this century: the iPhone, social media, Uber, sat navs, YouTube, Deliveroo – even flat whites!

All these are disruptive innovations that have turned upside down aspects of the way that we live and function. It would be hard now to imagine routinely taking our photographs to be printed or using a book of maps or a telephone directory (or even a phone box). They have been fundamentally disruptive.

Hold on to that thought.

The internet is currently alive with insight pieces about learnings from the experience of COVID. There is a clarion call to ‘build back better’. This blog is another of those. We would say this, of course, but this one’s a bit different in a couple of ways.

The first is that our work draws from four totally different fields of public service experience impacted by COVID and extracts common findings from across the four. The second, probably more significant, is that the insights derive from 12 workshops involving more than 100 frontline practitioners and system leaders across all 10 Local Authorities in Greater Manchester – a systemic and cumulative learning conversation in three phases:

- What innovations have inspired you and what can we learn from them?

- What more can we learn from similar innovations elsewhere in the UK and internationally?

- What messages does all this hold for the future?

There is lots more background: the themes (early help, community hubs; homelessness and early years – high needs); the methodology; the extraordinary level of consensus; even the anecdotes, but this is the first in a blog post series, so that will all have to wait for another time. This piece will start at the end and get straight to what we learned.

How did we learn what we learned?

There was no shortage of fascinating stories. From 100+ people working on the frontline of the emergency response who saw first-hand the changes to practice, to relationships and to decision-making. All this was processed in multiple ways, like the ingredients of baking, really – by service area, obviously (the separate ingredients) and then these were mixed into a generic architecture that spanned the service areas (leadership and governance; workforce and culture; citizen’s experience; system conditions). Finally, all this was baked (apologies for the metaphor) to reveal a unique set of insights.

And what did we initially think we had learned?

An initial trawl surfaced four overarching insights that together tell a powerful story about this unique moment. They derive from Greater Manchester and have universal relevance. Regardless of the service area or the context, these four ingredients created a context for rapid and potentially seminal innovation:

- A mission-driven unity of purpose.

- A humanitarian focus on places and people and their needs.

- A permissive and risk confident culture.

- The liberation and connection of previously latent local capacities.

Three of these are about new, liberating conditions. The fourth is about new capacities and changed system dynamics. All are empirical and multiply validated – and they are motherhood and apple pie. You could frame these four differently and say that all great local systems have a strong and unified mission, a clear focus on human need, enabling cultural conditions and that they liberate and align local leaders. (Job done!)

The message might be that COVID merely accentuated and galvanised the best of what we know to be good. Or finally brought it from paper to practice, at scale. That would be worth knowing, but there had to be more.

So what did we really learn?

In the final round of workshops participants considered what, from their experience of the emergency response, they would want to keep, amplify, discard and create in public service design going forward. The outcomes of this proved to be the most powerful, the most grounded and the most visceral of all the exercises. There were minimal sectoral differences and very high levels of consensus, and this led to a more radical set of big ideas:

- Dissolve sectoral and organisational boundaries – which might mean creating leadership roles that span service directorates; aligning sectoral missions and goals; sharing data and resources; devolving decision-making; introducing participatory governance.

- Abandon services and programmes – build out from people and their needs; provide help where people live; respond without thresholds; blend digital and face-to-face access; ensure a dynamic, multi-disciplinary response to need

- Empower communities – recognise hyper-local and self-defined communities; introduce joint and community commissioning and procurement; make providers accountable for co-produced, locally determined outcomes; manage and minimise external regulation.

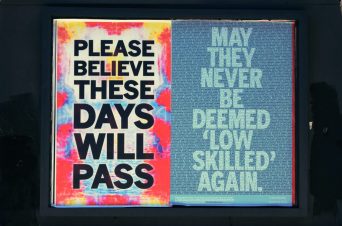

- Create a community workforce – hire diverse, community-based teams; recruit and train residents, VCS personnel and officers/practitioners as colleagues; adopt co-production as a core and common practice; support flexible home and community-based working.

Innovation is supposed to be disruptive

Remember the Stephen Fry examples – sat navs, social media, the iPhone etc – and their disruptive impact? Well, that’s what innovation does. It disrupts old ways and either transforms them or replaces them.

Stuff happened during the pandemic that has excited people about new possibilities and perhaps for the first time, made them feel plausible. If COVID is to be the great disrupter of local systems and services, then action will be required to keep this window of plausibility open. Local and national systems will have to address issues of power, money, risk and relationships that have become unhelpfully and unquestioningly entrenched.

So, if “abandon services and programmes”, or “create a community workforce” sound radical, then maybe they are no more dramatic and no less achievable than saying “replace books of maps”. There is a new way.

Is there a moral to this tale?

But – and isn’t there always a ‘but’ – the attentive reader may have noticed a couple of things about use of the Stephen Fry examples as analogies. One is that they are all (except for flat whites) examples of innovations driven or enabled by new technologies. The other is that they are all (even flat whites!) innovations entering from the outside. That means they were able to be introduced initially at the margins of the status quo, establishing themselves there with early adopter user groups, before growing and in some cases virtually replacing previous practices (think email and postal mail). They are not transformations designed from the inside to replace existing practices. That is much, much harder.

And that is where the moral lies. It is exactly why the COVID experience is so seminally important. We have had forced upon us a moment in time when business as usual has been suspended and, unwelcome as it has been, this has yielded a gift of evidence about the plausibility and efficacy of radically different ways of doing things. Our 100+ workshop participants were in no doubt about that.

Truth is that (apart from a natural disposition towards regressing back to organisational norms) there has never been a more opportune time to commit to transformation to sustaining and growing the best from this COVID disruption. It means not a journey to ‘build back better’, but to ‘design forward differently’. What might this involve? Well, here are six ideas drawn from our work with Greater Manchester:

- Follow the energy lines – go where energy for new ways of working has become manifest.

- Work with the ‘new leaders’ who have emerged through the COVID work to prototype approaches to sharing power, risk and resources on behalf of the rest of the system.

- Create a new ecosystem of place which recognises the significance of ‘local’.

- Create flexible, interim local governance arrangements to give new collaborations legitimacy, support and ideas.

- Devolve some resource to this level, both financial and human, to incentivise and enable – and make one of the new leadership roles a ‘community connector’.

- Secure an external partner who will both facilitate and ‘hold you accountable to your aspirations’ when the desire to regress feels irresistible.

Finish with a story

Everyone we spoke to throughout this project said that leaders and leadership had changed, by which they meant the way that senior leaders functioned during the COVID response. Senior leaders had never been so close to the front line, never so approachable, so visible, or so open to new possibilities. “Whatever it takes” and “Just do it” were phrases we heard a lot. What became apparent was that COVID had divested them of the prison of their personas.

As one participant put it: “When you are on Zoom and not in your office in a suit behind a desk, but at your kitchen table in a casual shirt like everyone else, the human face of leadership is displayed.”

Who would have thought it?

David Jackson and Julie Temperley, senior associates, Innovation Unit

In further blogs we’ll be exploring what our learnings could mean for: practice and citizenship experience; workforce and culture; leadership and governance; and system conditions.

You can read the full report here and follow us on Twitter @Innovation_Unit for updates.

For more information on Innovation Unit’s work, please contact Julie.